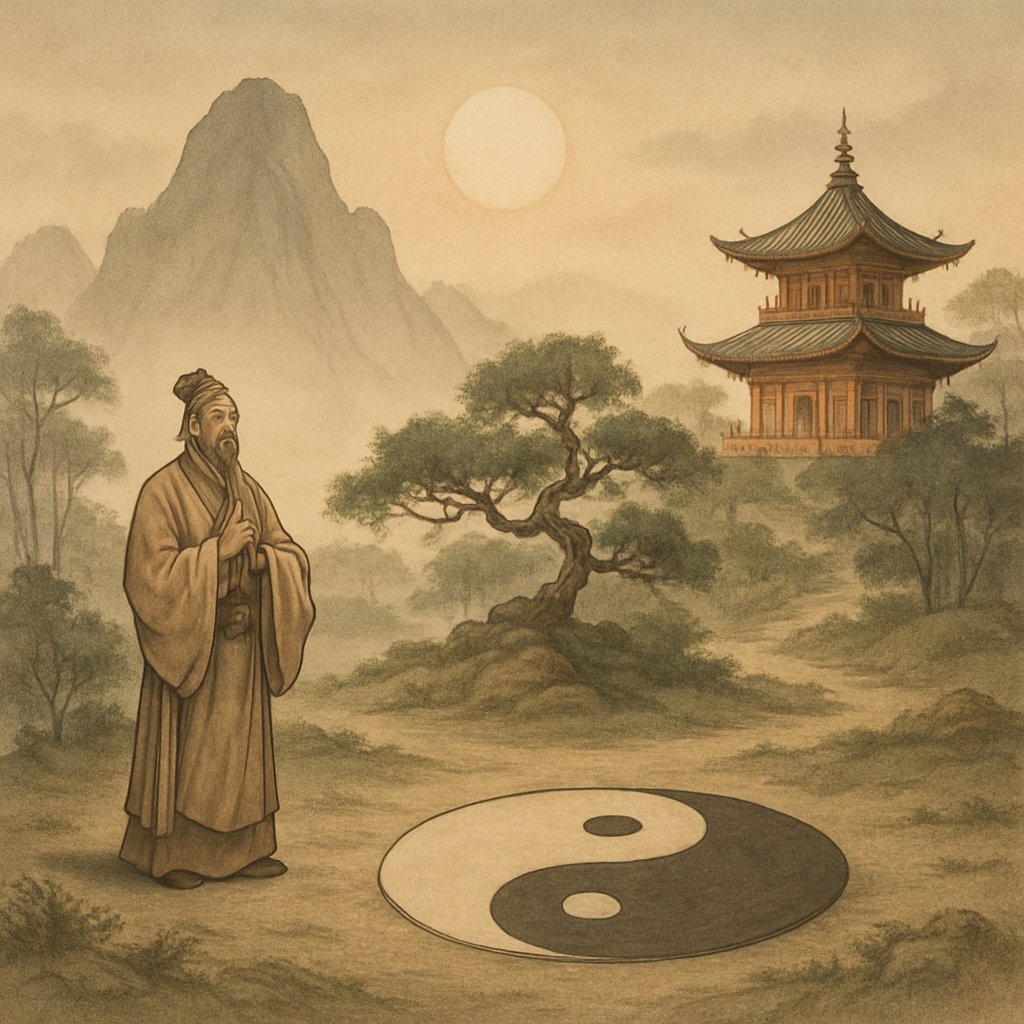

Discover the core principles of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, and their influence on modern Chinese life, education, and governance.

Discover the core principles of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, and their influence on modern Chinese life, education, and governance.

Explore essential tips for first-time visitors to China, covering visas, payment methods, language basics, and cultural etiquette.

Explore how modern urban projects can conceptually integrate the legacies of the Tang, Song, Ming, and Qing dynasties into contemporary design.

Dive deep into the world of dim sum, exploring its rich culture, essential etiquette, and must-try dishes for an unforgettable yum cha experience.

Explore the legacies of the Tang, Song, Ming, and Qing dynasties, highlighting their achievements and lasting impact on modern Chinese identity.

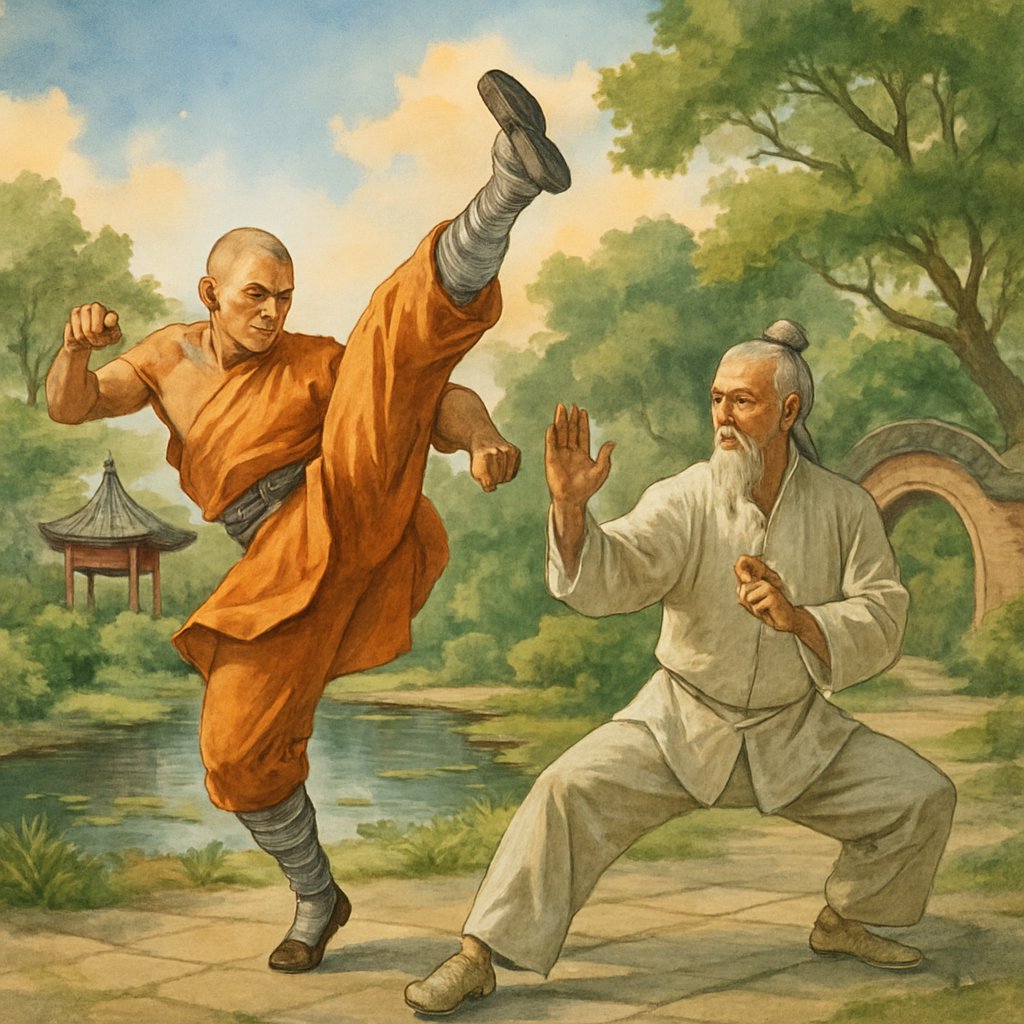

Explore the history, styles, and philosophy of Chinese martial arts, from Shaolin kung fu to Tai Chi, and their cultural significance.

Discover practical insights on living in China as an expat, covering costs, culture shock, and how to adapt successfully.

Explore traditional Chinese festivals beyond New Year, including the Lantern Festival, Qingming, and more, uncovering rich customs and foods.